Stan Christodoulou was the third man in the ring when Arnold Taylor, the baker from Jeppe, and Mexico’s Romeo Anaya went to war. It was Christodoulou’s first major assignment as referee, for the world bantamweight championship. Twenty thousand adoring fans packed the venue.

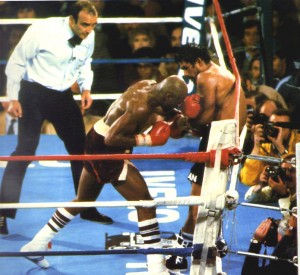

What happened next could have come straight from a Rocky movie. The two fighters engaged in a battle that assaulted the senses. Back and forth it went with Taylor, his lips lacerated by punches and his right eye closed, getting the worst of it.

Four times the bloodied Taylor dragged himself off the canvas, but in the 14th round he summoned his final reserves and crushed a desperate right against Anaya’s jaw that sent him reeling, unconscious.

Eugene Labuschagne’s black and white image of Taylor, his head arched back with arms aloft while Christodoulou administers the cold count, remains one of the most vivid photographs in SA boxing history.

‘I felt God’s hand was on my shoulder,’ said an exhausted Taylor, SA’s first world boxing champion since Vic Toweel 23 years before.

For Christodoulou, his first world title fight was a blur of emotions. Thrown into the turmoil of an extraordinary fight he wasn’t even supposed to work – the original referee, Harry Gibbs, was unable to make the trip – it demanded every bit of energy, good sense and judgement from him. It was the ultimate test for Christodoulou.

Ring magazine would go on to name it the greatest bantamweight fight of all time. The UK’s Boxing News ranked it among the 15 best fights ever.

‘I was blessed,’ remarked Christodoulou who, even now, four decades on, considers it the greatest fight he has been involved in. ‘A fight like that could never happen again; it was too brutal. Taylor looked like he’d been hit with a baseball bat.’

Years ago, Christodoulou was named one of South Africa’s most sexiest men. But that was long ago. Today, at 69, he is balding and heavy-set. Yet his smile and demeanour haven’t changed and he retains remarkable enthusiasm for a sport that has given him much.

He is a natural raconteur and the stories and anecdotes tumble from his lips faster than Floyd Mayweather Jnr delivers smacktalk. Just as well he is putting the finishing touches to his book: it promises to be a marvellous voyage through boxing’s surreal and often crazy world.

Born in Brixton, Stellianos Christodoulou would have had no idea what his life held. The son of Cypriot immigrants, he fought successfully a dozen times as an amateur, but broke his hand and that was that. Not that he wasn’t prone to scrapping outside the ring. He once brought traffic to a halt outside the old Roxy Bioscope in Brixton when he and a local Afrikaans rival rolled up their sleeves and got busy. ‘They made us tough on the west side of town,’ he laughs as he recalls the memory.

Aged 17, he attended a tournament in Standerton. Some match officials failed to arrive and Christodoulou, never short of confidence, put up his hand. He judged eight fights that night.

He was soon handed his licence. He hot-footed it all over the country, judging the likes of Eddie Ludick, Hottie van Heerden and Johnny Wood. Two years later he refereed his first fight. Three thousand-odd fights later, he is still refereeing, not to mention the countless judging assignments he has packed in around the world in the past 50 years.

Back then, he might have been raw and unsure, but he matured into one of the finest, most assured officials of all. He always said the best compliment you can pay a referee is to say you never noticed him. This has been unfailingly true with the veteran fight man. He possesses an almost serene presence, but his control is absolute.

His knowledge of boxing’s regulations is excellent, to the point that he makes split-second decisions without hesitation. He is the ultimate man in the middle.

Not that his career has been without controversy. He once got caught up in mayhem in Thailand when 7 000 fans went on the rampage after the main bout was cancelled. Another time, he had to take evasive action when a cornerman of title challenger Soon Yun Chung stabbed at him with a pair of scissors at the start of the 12th round. Local police dragged the attacker away.

In a similar incident in the Victor Galindez-Mike Rossman fight, Rossman’s father pulled a knife after Rossman’s brother had tried to attack Galindez at the end of the fourth. As ever, Christodoulou calmed matters and Galindez went on to win in the ninth.

In the late-1970s, Christodoulou found himself in South Korea for an Antonio Cervantes fight. Two locals knocked on his hotel door and asked to be let in. The one pulled out an envelope and flashed $10 000. Christodoulou was scoring referee for Kwang-Min Kim’s challenge and the visitors wanted to make sure their man prevailed. Not only did the South African declare the attempted bribe, he offered to withdraw.

Christodoulou has always worn his heart on his sleeve, never more so than the night Brian Mitchell captured the world junior-lightweight championship against Alfredo Layne in 1986. Sanctions were at an all-time high and it was a dark time for SA sport.

Apart from Mitchell pounding the Panamanian in the 10th round, the highlight of the fight reel is the sight of Christodoulou thumping the canvas again and again in unbridled joy. He may have let his guard slip, but that moment perfectly captured the zeitgeist.

The remarkable thing about Christodoulou’s officiating career is that much of it ran parallel to his job as executive director of the SA National Boxing Control Commission. For 29 years he was No 1 in SA boxing.

The day he walked in he cancelled the licences of 50 boxers, many of whom were medically unfit, setting the tone for his reign. The buck stopped with him and he always ensured governance was first class. Controls were severe under his watch and his manner was never less than authoritarian.

He got up people’s noses with his strict manner, but if some never liked him, SA boxing was never stronger or better run.

‘If I get it wrong, blow smoke up my arse,’ he would tell people. ‘Otherwise, let me get on with it.’

Today the administration is a shambles. Little wonder people often plead for Christodoulou’s return. His anger at the state of affairs is palpable.

A pair of presidential awards, one from FW de Klerk and another from Nelson Mandela, attest to his excellence.

His enduring class was never best illustrated than in 1999 when Evander Holyfield fought Lennox Lewis for the heavyweight championship. Two of the judges went against the overwhelming view that Lewis had dominated the contest – the fight was controversially declared a draw – with only Christodoulou turning in a card that reflected the truth. It was a scandalous result, but the SA official was lauded internationally for getting it right.

‘I was just doing my job,’ he explained. He has worked some of the biggest fights in history. The Richie Kates-Victor Galindez clash in Johannesburg in 1976 – black against white – could have had a messy denouement, but instead all the drama was centred on the fight, watched by 38 000 fans.

Blood gushed from Galindez’s mangled eye socket and Christodoulou’s shirt was drenched in crimson as the pair savagely fought. (For many years later, the shirt hung unwashed in a frame at Christodoulou’s downtown office.)

Galindez stalked Kates and knocked him out in the last minute. When Christodoulou reached the count of 10, there was one second left of the primal 15-rounder.

‘Night of the Animal,’ screamed the Sunday Times.

It was a fight that opened many doors for the South African.

His ability to read a bout, and indeed the fighters themselves, is without compare. Just a few months ago in Russia he refereed the Denis Lebedev-Guillermo Jones cruiserweight championship fight.

Lebedev suffered a grotesque cut and swelling around his eye, but as bad as it looked, Christodoulou was satisfied with Lebedev’s condition. Although the Russian was finally stopped near the end, Christodoulou took heart from the fact that he had been leading on the scorecards. He had given him every chance to win.

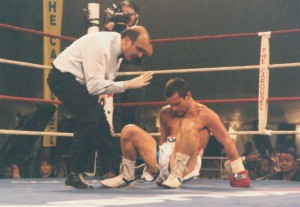

Exactly 30 years ago, Marvin Hagler’s encounter against Roberto Duran was the biggest of all time, breaking gate receipt and television records.

Christodoulou was handed the plum assignment, drawing praise for his handling of the frenzied 15-rounder at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas.

The contest ranks among the biggest of his career, but then the Alexis Arguello- Aaron Pryor and Tommy Hearns-Pipino Cuevas fights, both of which he refereed, were also in the league of superbouts.

The first was 1982’s Fight of the Year and again Christodoulou was praised for his perfectly-timed late stoppage.

Each time he was appointed in the ’80s he had to fight to keep the honour because of his South African passport. Pryor, a black man, said: ‘I judge a man on his reputation … I want Stan.’

Christodoulou always fought for nonracialism in boxing, but sometimes it was never enough.

Assigned to the Davey Moore-Duran bout on 16 June 1983 (the anniversary of the Soweto uprising), little was he to know what was to come. It was another famous bout at the iconic Madison Square Garden. As Christodoulou sat in front of Muhammad Ali, who was teasing him by blowing into the back of his head, the excitement heightened.

Then Christodoulou was told of demonstrations outside. Moore wanted to keep him as third man, but he was overruled. With 20 minutes to go, Christodoulou was thanked for his trouble and sent on his way.

Still immaculately dressed in his bowtie and boots, he trudged back to New York’s Waldorf Astoria. ‘Easily the low point of my career.’

Yet such dark moments were few. Christodoulou was to find himself in a few more classics yet. In 1994, he was third man in another Fight of the Year when Jorge Castro and John David Jackson produced a classic. Jackson pounded Castro throughout, but Christodoulou could still see the fire in his eyes and when Castro slammed home a crushing left hook in the ninth, he was vindicated.

‘Miracle in Monterrey’ blared the headlines.

So many more special moments rush through Christodoulou’s mind, a blend of fighters, celebrities, camera flashes and lights and music.

‘Nothing compares with a heavyweight superbout,’ he says. ‘All the stars come out to play. It’s very special.’

Fittingly, his 200th world championship assignment took place east of Johannesburg a few months ago when he refereed the Hekkie Budler-Nkosinathi Joyi fight with usual quiet authority.

He’s admittedly had a few howlers. In 1986, on the undercard of Simon Skosana’s failed world title attempt at Rand Stadium, he copped one on the nose. Keeping his wits, he somehow stayed on his feet.

Years earlier, a mistimed shot by Mike Schutte landed on Christodoulou’s chest, but the referee was too busy warding off chaos – Kallie Knoetze was the opponent – to notice at the time. His body ached for days afterwards.

Approaching his seventh decade, Christodoulou might be slowing down. He doesn’t do roadwork nearly as much as he used to and the travel sometimes gets him down. But his excitement and enthusiasm is undiminished, his admiration for fighters unending.

‘I’ve been really lucky,’ he says from his home in Ballito on the KZN north coast. ‘I loved the sport as a child and it became my career. The places I’ve been, the people I’ve met … you can’t put a value on that. I’m very grateful.’ And so are we.

Van der Berg is communications manager for SuperSport, a former SAB Sports Writer of the Year and a regular contributor to Business Day Sport Monthly.